HOTEL DU CENTRAL

St. Severin tolls on the corner.

Thieves huddle by its gates.

Monsters perch on its eaves.

Across Rue St. Jacques you bathe

in the cold water flat

saying how Paris wastes our days.

We linger in the sidewalk bar,

use callous words.

You’ve grown restless

in the market on the boulevard.

You tap your ashes in coffee cups.

Peculiar maps, peculiar times.

Tickets in a foreign tongue

lie heavy in your clothes.

Go then. Be a tramp in Italy

or tanned and laughing in Greece.

The city turns cold.

And Paris, thief of thieves,

comes in the loud

night to steal the last

strength in my legs.

OK, I’m tired.

Take what you will.

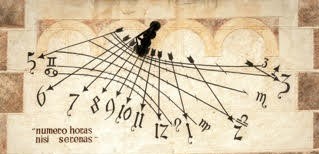

MAPS HAVE NO TEARS TO CRY

Lands struggle to stay afloat

Grasping for each other.

Twisted faces, agonized,

Change shape only in eons.

Within grotesqueries

Neighbor abhors neighbor.

Black lines

Carve the maps.

Maps carve the world.

TIDES

Hoary gods in service to the moon

Spill their marrowed tears on shelled

Sands, bone longings of our white days.

Electric strings of eye, and ear harrowed

White with spectral winds or breezes

Tinged iodine in their anger, fierce and

Filled to the brim with lurid nerve,

Pull at the hem of our legendary hearts.

IN MAGNETIC BLOOD

Magnetic blood.

Where liquids swell to mythical

height.

Shoulder blades break from flesh, bare as wings in rawboned

sun.

Secret muscles expand.

From pole to pole the earth sings in lean darkness.

The compass flexes.

Ice and fire rush through veins. Stars beat like hearts.

Genetic codes click on winds past Olympia.

Under sunny skies the Word is made new.

The Mathematical Rose

whirrs in its clean language while the temperatures of atoms quicken.

Mythic creature — you and I

(two cruel Michelangelos) pass judgement here on the human form.

The Worm and the tides — in their fusion feel the swell,

the swell of hot

magnetic blood.

OLD MARKETPLACE OF ROUEN

lambent flames

fold ‘round the girl

who does not

scream. dawn’s

cello bows a bleak

sonata as ash rises.

Rouen holds black

bones. what once

beauteous, now

vile in the sky.

mark on all who see,

pitch on ashen souls.

dust for loins, legs

gone to black sticks,

eyes boiled to bone

stare, the girl who

wanted more than lace

& pretty shoes to wear.

IN GRAVITY’S THOUSAND ARMS

Slaves of the tide and its skyward house

we march in bones from one beginning.

Wars between the man and woman rage

like suns in the throat of some hot God.

Gardens fashioned with words in the world

tell the summertime of perfect Eve.

Bless the wheel driven from Paradise,

all the beasts making peace with Adam.

But gravity tugs at the blood

curving at the speed of light.

If the world has a ladder

it is the act of loving.